Weather routing is a bit of a chess game against the weather-at times, it can be more dangerous than you’d like (published September 2012)

It’s a chess game. You—or me—against the weather. It matters little whether I’m on a race or delivering a boat; trying to set a speed record or routing someone else; on a monohull or multihull; dealing with novice crewmembers or battle-toughened offshore veterans. There are different constraints, assets, liabilities and mission statements, but it all comes back to playing a chess game against the weather. Sometimes I win, sometimes the weather catches me.

Paul Cayard, following a victory years ago in the Whitbread Round the World Race, responded to the congratulations being offered with this observation: “I’ve actually lost more races than I’ve won.” By learning from our losses we turn our defeats into victories and come back stronger. Just don’t lose a chess game against a hurricane.

When people ask what prompted me to get involved with marine weather routing, I tell them that in 1985 I did a singlehanded trans-Atlantic speed record attempt/delivery aboard Thursday’s Child as a qualifier for the ‘86-’87 BOC. I confronted the worst weather I have experienced in the North Atlantic, and placed myself on the wrong side of every wind shift. For 23 days I was alone and had ample time to reflect on the concept that there had to be a better way. Since the question about my initial interest often comes up while I’m offshore, people don’t always feel particularly comforted by my story, but somehow it makes me laugh. Shortly after that 1985 experience, I started to take a proactive role in learning how to best deal with weather in a marine environment.

When people ask what prompted me to get involved with marine weather routing, I tell them that in 1985 I did a singlehanded trans-Atlantic speed record attempt/delivery aboard Thursday’s Child as a qualifier for the ‘86-’87 BOC. I confronted the worst weather I have experienced in the North Atlantic, and placed myself on the wrong side of every wind shift. For 23 days I was alone and had ample time to reflect on the concept that there had to be a better way. Since the question about my initial interest often comes up while I’m offshore, people don’t always feel particularly comforted by my story, but somehow it makes me laugh. Shortly after that 1985 experience, I started to take a proactive role in learning how to best deal with weather in a marine environment.

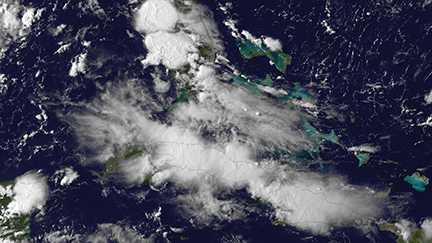

One of my more interesting chess matches happened during hurricane season a few years ago. It was September, the worst month of the year for tropical disturbances in the Atlantic. Isbjorn was a sloop-rigged mini-maxi racer-cruiser. Impeccably maintained for years, the aluminum-hulled vessel was lying in Norway and needed to be moved to Newport, RI for a brief refit prior to going to the Caribbean for the winter. The owner of the vessel, a friend and well-respected sailor, contacted me. He needed to know if I could help the captain bring the boat from Europe. There were already three named tropical disturbances in the southern part of the North Atlantic. Chances were good that they would be making their way north, along the eastern seaboard and then heading east across the northern North Atlantic—right along our track. The captain of the vessel was also a friend with whom I had already completed trans-Atlantic passages, and I knew that he and the boat would be well prepared.

My first thought was that it might be better to wait until November and take the boat directly to the Caribbean. A minor refit was in order, however, so that option was eliminated. Departing from Norway, we had two initial options. We could pass north of the British Isles and take an initially shorter-looking course along the Great Circle back to Newport. Alternatively, we could drop south through the North Sea and English Channel and take a more rhumbline course across the Atlantic, trying to keep the Gulf Stream to our south to avoid its adverse current. Although the more southerly route initially appeared to add miles to the passage, we opted for it. If we took the northern route, we would be directly in the storm track. If problems arose, we could have been forced up against the Greenland coast in storm conditions. Additionally, that route would have taken us into prevailing southwesterlies for the last half of the trans-Atlantic passage. We could have been forced to beat into storms with little room to run off in the event of a full-blown hurricane.

We made good time moving through the North Sea and broad-reached south in the northwesterlies. After motoring a bit in the English Channel, we stopped in Lymington, England to top our fuel tanks and add a few provisions. With favorable weather at the start of the ocean crossing, we reached over a cut-off low-pressure system that was parked over the Azores. Halfway across the ocean, the chess game with the weather grew a bit more intense.

All three tropical depressions developed into hurricanes. Two of them had already come ashore, degraded into extra-tropical depressions when cut off from the warm water’s energy source, and passed to our north. They went right down the storm track as we’d suspected. Had we opted for the northern route, this story could have been much different.

All three tropical depressions developed into hurricanes. Two of them had already come ashore, degraded into extra-tropical depressions when cut off from the warm water’s energy source, and passed to our north. They went right down the storm track as we’d suspected. Had we opted for the northern route, this story could have been much different.

The third hurricane was a bit more problematic. We were in daily communication with Commanders’ Weather, and when the hurricane appeared about five days from our position, they projected that it would actually pass quite a bit further away from us. Their forecast had the hurricane making landfall about 60 miles east of Halifax. The National Hurricane Center and our daily weather faxes progressively forecast the track to get closer and closer to us. With the hurricane about 400 miles away, according to the NHC, we would eventually be in the leading right-hand quadrant of the hurricane if we didn’t take evasive action—the worst sector to be in. The speed of the system would increase as it went over cold water and hooked up with the jet stream, even though its intensity might diminish slightly.

With the Gulf Stream to our left (south), it was time to make our move. Had we gone earlier, the hurricane might have made a sudden, unforecast turn to the east and we would have headed into the raging system. With only 24 to 36 hours to closing with the storm, the track forecast was becoming more reliable. By turning to the south and crossing the Gulf Stream, both the NHC and Commanders’ Weather forecasts would put the hurricane to our north. Commanders’ still believed that the depression would make landfall about 60 miles east of Halifax, which would be about 700 miles from our projected position. According to the NHC, if we maintained our new southerly course and speed, we would be about 250 to 300 miles from the hurricane—outside of its worst effects. We kept monitoring the storms’ progress, cleared everything possible from the decks, readied storm sails, prepared for heavy weather down below and made sure that batteries were fully charged.

As the next 24 hours wore on, we were pleased to see that the forecast from Commanders’ was almost perfect. While we rode up and down on 25-foot high, long period swells like one elevator ride after another, we were glad that the hurricane was actually making landfall 50 miles from Halifax—a mere 10 miles off Commanders’ original five day forecast! Observations recorded 100-foot waves off the Canadian coast. If we had opted to try to run into St. John’s and were late, it could have been a disaster. By electing to remain current with the forecasts, keeping plenty of sea room between us and the most adverse forecast position for the hurricane, and carefully planning our moves accordingly, we were able to make a reasonable showing in that particular chess game with the weather.

It’s true enough that we could have saved a bit of time if we had held our original course for Newport, but flying in the face of a National Hurricane Center forecast seemed rash, to say the very least. When it comes to hurricanes on deliveries, planning to avoid a worst case scenario is the approach to take. But while we were making those choices, you can be assured that our entire focus was on options, probabilities and choices. The chats among the crew, while calm and measured, were certainly focused. And to this day we all enjoy the opportunity to sail together whenever possible.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net.

Tropicals

Tropical storms (or tropical cyclones) are warm storms. They feed on warm air and energy from warm water. The warmer and moister the air, the more the storm intensifies, assuming that upper atmosphere wind shear is not an inhibiting factor.

Tropicals generally are smaller than extra-tropical storms (only 100 nm to 400 nm wide). With severe tropical cyclones or hurricanes, the only hope for the sailor may be to route around them. With large extra-tropicals, the size of the system may eliminate that option.

The strongest winds are closest to the center of the system. They may have a very distinct eye as they develop.

Tropical storms do not have fronts associated with them.

Extra-tropicals

Extra-tropical systems are a mixture of warm and cold air. They intensify when warm, moist air mixes with cold, dry air. The greater the temperature contrast, the stronger the storm.

As a result, there can be occasions when a warm, moist tropical storm recurves to the north and mixes with an extra-tropical system containing cold, dry air. The added warm, moist air from the tropical system increases the temperature contrast in the new combined system and the whole system acquires extra-tropical characteristics.

Extra-tropical systems are often 500 to 1,000 nm across.

The strongest winds are often located away from the center of the storm, especially as the extra-tropical system develops into a more advanced stage.