Tropical weather systems, and hurricanes in particular, have their own idiosyncrasies. Understanding them can help us deal with them more effectively. Misunderstanding them can be a disaster (published September 2016)

It was 7:30 p.m on a Sunday evening. The phone rang. Lia Ditton, a woman with whom I have sailed extensively and weather routed across the Atlantic, was calling from Hawaii. A highly experienced long distance and shorthanded sailor, she is also an experienced transatlantic rower. Now, the Safety Officer for the Great Pacific Race, a rowing race from San Francisco to Hawaii, she wanted to discuss the current hurricane situation in the Pacific. With a fleet of rowers and a series of tropical storms out there, the mix could be a big problem.

Putting hurricane realities into perspective, it should be mentioned that the weakest level of hurricane has 74-95 miles per hour winds. The strongest is in excess of 157 miles per hour. In 95 miles per hour winds the wind strength prevents people from walking upright. Who would want to? On land, with lawn furniture and BBQ grills flying through the air, the upright person would present a larger target for a multitude of lethal missiles unleashed by the wind! Offshore, a person trying to walk upright could easily be blown overboard. Crawling becomes an option. It’s not a great one! A stunning fact, however, is that in many places, it’s the water that accompanies a hurricane which creates the most devastation. Whether one is rowing or sailing a boat, the seas become an avalanche of water. If “knowledge is power”, knowing a bit about hurricanes can help us avoid— or at least prepare for—the worst of it.

INTRODUCTION TO HURRICANES

INTRODUCTION TO HURRICANES

Weather is a complex operation with a wide range of variables. Tropical low pressure systems, as an example are quite different from extra-tropical lows—lows that are predominant in areas outside of the tropics. Hurricanes often start out as tropical waves, becoming tropical depressions, lows, and storms if conditions are suitable for development. A variety of criteria must be met in order to progress from tropical storm to hurricane strength.

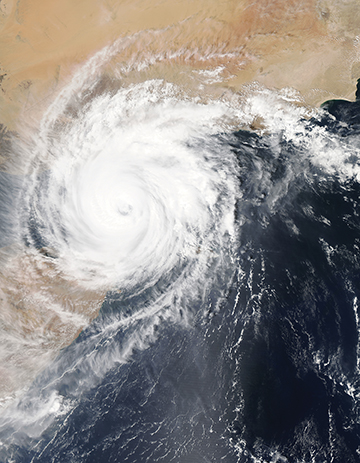

During the initial stages of a tropical low pressure system, there will be a disturbed area with clusters of thunderstorms. In the Atlantic, as an example, the clusters could be along a tropical wave in the isobars of surface pressure that originates in northwest Africa or along an old cold front that can occur anywhere from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to the Bahamas into the Gulf of Mexico. In the Pacific, the spawning ground for tropicals is often Mexico or Central America with its associated heat. As the tropical wave develops into a tropical depression, the thunderstorms organize, and an area of surface low pressure forms. The thunderstorms converge towards the center of lower pressure. In the Northern Hemisphere, the thunderstorms spiral in a counter-clockwise direction. In the Southern Hemisphere, the thunderstorms spiral in a clockwise direction. When sustained winds are less than 35 miles per hour, the tropical low is classified as a tropical depression.

In order for the tropical depression to continue to develop and become a tropical storm, the inflow of thunderstorms and warm humid air must increase. The pressure continues to fall, and sustained wind speeds must exceed 35 miles per hour. At that point, in the North Atlantic, a tropical storm is named. Although naming protocols vary in other parts of the world, in the North Atlantic and both the Eastern and Central North Pacific, each storm is named alphabetically beginning with “A” for the first storm of the new calendar year. In the Western North Pacific, the alphabet is not restarted at the beginning of the new year. Rather, the alphabetical process proceeds through “Z” and restarts at “A” without regard to calendar years. Additionally, some parts of the world refer to these types of storms as “tropical cyclones.”

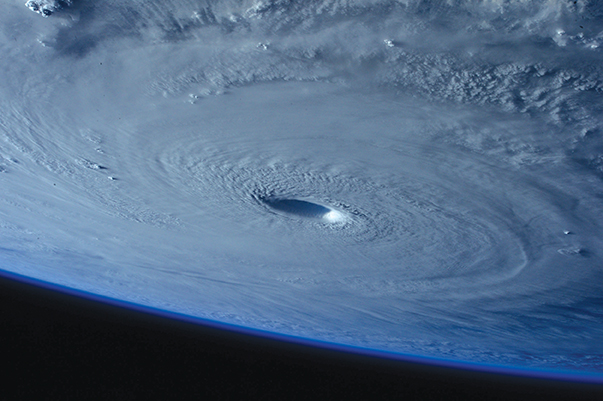

With clouds and warm, humid air inflows continuing to build, the center barometric pressure continues to drop. An “eye” is likely to form at the center of the low pressure system. In order to continue storm development into hurricane strength, sea temperatures need to be at least 81 degrees Fahrenheit. Tropical systems become classified as hurricanes when sustained winds reach 74 mile per hour. Warm water provides the energy that fuels the convective system. The warmer the water, the more energy is available for hurricane strength to develop. The moist air and clouds in the vicinity of the system allow for efficient transmission of that energy. And the lack of wind shear aloft, allow the convective system to develop fully, reaching higher altitudes and colder temperatures aloft.

Because there are various elements that go into building the strength of a tropical depression, storm or hurricane, if any of these critical elements are removed, the systems can lose some or all of their strength. As a hurricane goes over land, as an example, it loses its primary source of energy—the warm ocean. Warm air is often replaced by cooler air at the system’s lower altitudes. Additionally, the increased friction over the surface of land slows the inflow of energy into the convective system. Dry air is introduced, instead of the moister air of the ocean, so fewer clouds are created. And strong wind shear aloft from wind currents such as the jet stream will tear the vertical structure of the storm apart.

Although tropical storms have been recorded in the North Atlantic in every month of the year, hurricanes have only been absent there during the month of April. The peak months for tropicals in both the Eastern North Pacific and North Atlantic are during the late summer —late August and September. That is when the water is the warmest and wind shear aloft at its minimum.

GENERAL TRENDS

Where hurricanes tend to form in the North Atlantic and how they tend to track, however, vary somewhat with the month. These are general trends, however, and not at all forecast routes. Each tropical storm will take on its own characteristics of development and track.

Hurricane tracks in the North Atlantic: June Considered early in the North Atlantic hurricane season, June tropical storms and hurricanes frequently form in the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. Their tracks generally take them into the Gulf States or across Florida and up the North American East Coast as they recurve towards Europe.

Hurricane tracks in the North Atlantic: July Still somewhat early for the North Atlantic hurricane season, July tropical storms more frequently begin their formation a bit further to the east than the June storms. Tracks often take the tropicals into the Gulf States or northerly along the North American East Coast before they recurve toward Europe.

Hurricane tracks in the North Atlantic: August With the peak of hurricane season approaching and the water temperatures of the tropical North Atlantic continuing to rise, August tropical storms and hurricanes form further to the east. They can form as far east as 40 degrees W. latitude or more. With the eastern formation, the hurricanes have more time to recurve back toward Europe without making landfall in North America.

Hurricane tracks in the North Atlantic: September September is the peak month for hurricane formation in the North Atlantic. Water temperatures are among the warmest of the year. There is relatively little wind shear present compared to other times of year, and clouds are plentiful. The hurricanes often begin as tropical waves undulating their way off the northwestern coast of Africa. Formation can take place as far east as 30 degrees W. latitude, giving the tropicals a great deal of distance to develop and/or begin a recurve toward Europe prior to reaching the islands of the Caribbean or North American continent.

Hurricane tracks in the North Atlantic: October As temperatures begin to cool the water in the tropical North Atlantic, hurricanes and tropical storms tend to again form somewhat further to the west or in the southern parts of the Caribbean. This is not meant to imply that they are less dangerous or potentially less destructive. Merely it is meant to say that climatologically, their main areas of formation and frequency are changing.

Hurricane tracks in the North Atlantic: November Early November is often considered the “end” of hurricane season. Offshore, vessels and captains departing the North Atlantic bound for the Caribbean often feel that the danger of tropicals or hurricanes is past. It isn’t. Remember that the only month in recorded history that doesn’t have a hurricane in the North Atlantic is April—and that month has had a tropical storm recorded as recently as 2003! With North Atlantic water temperatures continuing to drop in November, storm formation occurs more often in the Caribbean. Late season hurricanes tend to have somewhat erratic paths. Or, perhaps, another way of looking at it is that, with relatively little data from past late season tropical storms, their paths tend to be somewhat more difficult to predict. The hurricane that formed near Jamaica and went “backwards” into the trade winds 15 years ago, going over the British Virgin Islands, St. Maarten’s, and Antigua from the west towards the east, was a late season hurricane. Their tracks are difficult to predict and planning should take that into account. The tracks for Eastern North Pacific hurricanes are no less difficult to predict. (See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacific_hurricane)

Tracks are not the only aspect to a hurricane that is difficult to predict. Storm surges—the water that is pushed in front of the storm—are also difficult. The storm surge that hit New England in 1938 was well over 15 feet high, and they can reach 20 feet or more. If the tide is high at the time the surge approaches, the additional height can overwhelm bridges, docks and other coastal structures, including houses. Offshore, the storm surge is less discernible, but the waves that accompany the actual high winds can be similarly problematic for vessels at sea. Following the storm surge, which may only last six hours more or less, depending on the speed and timing of the system, rains will penetrate far inland, causing severe flooding and adding further reaching damage. Like the wind blowing BBQ appliances or shutters through the air, the storm surge and subsequent flooding can push boats, vehicles and other larger objects into bridge abutments or other structures. Planning needs to include the removal of all objects that can be carried by the severe winds, and anything portable should be move to high ground.

Of course, storm procedures are far more extensive than that. Vessels caught offshore need to take evasive action, getting out of the leading right-hand quadrant—the most destructive sector of the approaching hurricane. All loose gear and anything that provides unnecessary windage must be taken off the deck. All gear below must be stowed properly, keeping in mind that the vessel may be rolled upside down in extreme seas. Batteries should be fully charged. Crew must be fed and rested, and food, tools and emergency equipment must be both secure and immediately at hand. Knowing in advance when these preparations are required and when they aren’t provides a significant ability to manage both risk and costs resulting from potential damage.

WEATHER FORECAST

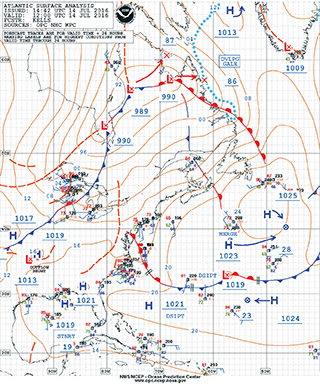

Weather forecasting became significantly more accurate in the mid- to late-1990’s with the increased availability of remotely sensed weather data combined with increasingly accurate weather forecast models. Satellites now circle the globe, providing relatively accurate wind speeds and directions and other observations in near-real-time. The European ASCAT data can be accessed online at http://manati.star.nesdis.noaa.gov/datasets/ASCATData.php/. Due to the fact that the data is observed and re-sent via Low Earth Orbiting (LEO) polar satellites, the swaths have periodic gaps in the data that is captured on subsequent orbital passes. Utilizing a number of models and a wide variety of data resources, the NWS’ National Hurricane Center provides a good baseline of current hurricane information on its site, located at: http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/

Weather forecast models have become increasingly accurate. However, having said that, they are far from perfect. Still the best sources of information are provided by a “man-machine-mix”, combining the far sighted analytical potential of super computers with the critical, subjective perspective of trained and experienced meteorologists. There is a wide range of computer-generated weather models from which to choose, and comparing off-the-shelf models with each other, one can quickly see vast discrepancies. Far better accuracy is generally achieved in the near term when a trained meteorologist “adjusts” the modeling results tempered by experience. The NWS’ Ocean Prediction Center at http://www.opc.ncep.noaa.gov/ provides man-machine analyses and forecasts for the North Atlantic and North Pacific. Alternatively, private weather forecasting services such as Commanders’ Weather at http://www.commandersweather.com/ provide high quality, site specific forecasts anywhere in the world.

You should be aware that GRIB files tend to smooth the data, severely under-estimating wind speeds. I’ve seen GRIB files that indicated maximum wind speeds in a particular hurricane and estimated those winds to only reach 45 knots! By definition, I knew that winds would greatly exceed that figure. Meanwhile, buoy reports indicated 120 knot sustained wind speeds. GRIB files will NOT provide accurate wind speeds for an approaching tropical storm.

On the “positive” side of the explanation, hurricanes are relatively small weather systems. The potentially destructive areas of a hurricane seldom measure more than 400 miles across. Given enough warning and reasonable mobility, vessels offshore can often sail around them—if they go the right way, and the predicted storm track is accurate. Rowers, of course have other significant limitations. Their speeds may only approach one and a half or two knots and they may only be able to row downwind or—at best—perpendicular to the wind. Regardless of the type of vessel, evasive action should be taken early as soon as the system’s predicted course is reliably known.

While offshore, I’ve seen the initial stages of a hurricane form overhead. I’ve watched them pass, several hundred miles away. And I’ve had one pass directly over the top of me—fortunately, from the cozy confines of home. Do yourself a favor: remain aware of the weather and avoid hurricanes entirely. They’re very bad news when you’re caught inside their grip, and they’re a weather pattern you don’t want to deal with in any type of vessel.

While offshore, I’ve seen the initial stages of a hurricane form overhead. I’ve watched them pass, several hundred miles away. And I’ve had one pass directly over the top of me—fortunately, from the cozy confines of home. Do yourself a favor: remain aware of the weather and avoid hurricanes entirely. They’re very bad news when you’re caught inside their grip, and they’re a weather pattern you don’t want to deal with in any type of vessel.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net.