What the grounding of the Team Vestas Wind boat in the Volvo Ocean Race reminds us about our own navigation (published January 2015)

We have long taught at Starpath School of Navigation that we should never blame echarts for anything that goes wrong. This is a fundamentally important rule that we see violated over and over again. Granted, there is much not to love about vector echarts—the ones called ENC (electronic navigation charts), as opposed to RNC (raster navigation charts), which are identical to their paper counterparts. Unlike the ENC, the RNC are updated weekly in print and echart at no charge. The rule applies to RNC as well, but they are not as often the brunt of criticism as are the ENC.

Vector charts are easy targets for blame. First, for general use in what is called ECS (electronic charting systems) there are no real standards in functionality and chart symbols, as opposed to ECDIS use (electronic chart display and information system, pronounced ek-dis), the professional system sanctioned by the World Hydrographic Organization. Sailors and other recreational mariners, however, do not often use official ECDIS software or charts. We use mostly ECS, which means simply any combination of echarts and software we might have. Some ECS strives for the ECDIS standards; others do not. The latest edition of the Chart No 1 booklet now includes many of the ECDIS symbols, which is a valuable free download to have. The full range of ECDIS standards is immense, as it also includes how the various aids and landmarks should be described, coded and indexed for display in various layers. There are also standards on the ECDIS software functionality, which is often not as convenient as some ECS programs. This is in part why manufacturers do not use it.

A big difference between RNC and ENC chart symbols is the legends explaining the symbols are all in print on the RNC, whereas in ENC we usually need to right click it or highlight it and press “Info” to learn what it means. This has lead to several incidents: I recall a racing yacht grounding on the West Coast that blamed echart symbols, as well as a tanker hitting a bridge in San Francisco Bay because light symbols were misunderstood.

And of course there is the appearance of the land that differs between these two chart formats, sometimes tremendously. All ENC start out as RNC that someone, or some software, manually or electronically digitizes. Eventually these might all be tested by satellite images, which is done to some level now. Certainly at some point the ENC will be better than the RNC, and I would venture that someday all charts will be ENC. It is the logical direction to go, just as print on demand was a logical direction for paper chart production. But for now, we will find more errors in the ENC charts than in the RNC, and more of them blamed for navigation shortcomings. ENC include all errors that might be in the RNC (from incorrect or outdated surveys) plus any new errors that come from the digitizing.

On the other hand, like any working database, the ENC will just get better over time as the errors are found and removed and new meta data describing the features are added. The attraction of the ENC comes from this great potential of including so much information, plus the fact that they are individually small files. Entire sections of an ocean basin can be included in one large file, including every harbor chart as well. Furthermore, we can have ENC charts for remote parts of the world where there are not many alternatives.

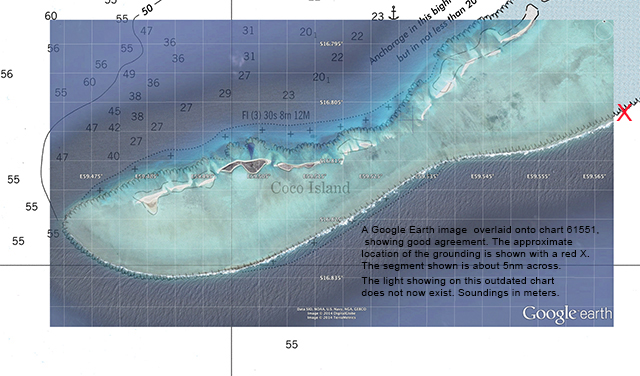

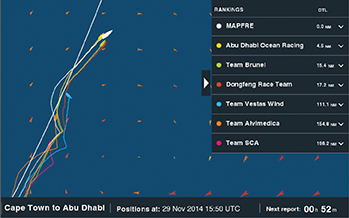

This last point came to mind immediately upon learning of the grounding of the Volvo Ocean Race competitor Team Vestas Wind on a reef at the southwest tip of Cargados Carajos Shoals on November 29th at 1510 UTC. All crew are safe, which is quite a blessing in that the GPS track of the vessel shows 17 to 19 knots of speed within seconds of 0 knots. The grounding was just off Coco Island, meaning they were five miles off course to miss the hazard and at least 10 for a safe passing at night.

This reef is in the quintessential middle of nowhere, about halfway through the 4,500-mile Leg 2 of the race in the middle of the Indian Ocean, about 216-miles north-northeast of Mauritius. But even though this is a remote location and a small group of reefs, islets and shoals, it is not at all a secret place. In fact, the entire middle segment of the Indian Ocean has the Cargados Carajos Shoal’s name written across it in large capital letters in the graphic index to the U.S. International Sailing Directions, Pub 171. It is Section 9. The Sailing Directions are the ocean counterparts of the Coast Pilots, and they have the same goal, namely to provide crucial navigation information that is not on the charts. For any long voyage it is fundamental that we check the Coast Pilots and Sailing Directions. In this specific case, however, we do not learn enough from the two paragraphs about this reef in the latest edition of Pub 171. In fact, the only chart of the area it refers to is DMA No. 61551, which has been out of print for about five years. It also has the confusing information that the southwest tip might be three miles southwest of where it is charted, then later says you can pass the southwest tip within one mile—presumably meaning from wherever it is.

Thus when planning a trip near this region we have to work harder. The natural next place to look is the BA Pilots, which are the British equivalent of the U.S. Sailing Directions, though famously more thorough and famously more expensive. Vol 39, South Indian Ocean is only $60; other volumes are twice that. They are in good libraries, however. Here we learn that BA chart No. 1881 has pretty good detail, and No. 4702 is a smaller scale showing the extensive gamut the yachts must face headed north across the Indian Ocean. The BA Pilot devotes two full pages to these shoals.

We do learn from both the U.S. and BA sailing directions that the Cargados Carajos Shoals should not be approached from the east (breaking waves obscure the location of the reef, which itself is only poorly known) and that the Shoals should not be approached from any direction at night. The four boats that passed the Shoals well to the west some five hours earlier did so in daylight, and at least one may have been close enough to see them, which are described as clearly visible with some hills to 70 feet with vegetation and a few low-lying buildings. This can be seen on Google Earth (GE). There are even some permanent residents there, including two Coast Guard personnel—very isolated, but in a very pretty place. Vestas Wind unfortunately came in from the east at night.

One other yacht passed well below one mile of the reef tip in daylight (too close for a navigation instructor, but not a racing tactician), and could have been lucky in light of the NGA warning about the southwest tip. Figure 1 shows the boat tracks. In daylight the closest may have seen the reef and its limits as they passed.

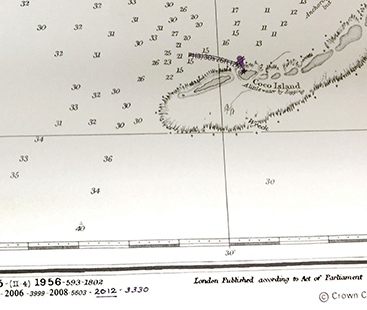

BA charts are available from all BA outlets worldwide (there are a dozen in the U.S.), and this paper chart is probably in stock at many outlets as it is part of a BA reseller requirement. The chart 1881 is the one of most interest here, being the basis of all other charts, and the navigation charting story begins with it.

This chart is essentially the same as it was in 1941, based on a survey taken in 1894, with periodic updates over the years, but no real surveying improvements. There is the discussion mentioned in the sailing directions and much online chatter about whether or not the shoals are where they are plotted, but we can compare with GE to see that it is indeed very close (Cover picture). This is not an issue. There is always the issue of having your GPS set to the chart datum of the chart, but that should be standard knowledge these days, and could account for hundreds of yards and rarely a mile. The out of print U.S. chart 61551 is essentially identical to the BA chart 1881 upon which it was based, but there is one important difference.

If you compare 61551 with a paper version of 1881 purchased from an authorized BA distributor, you will notice one main difference in the vicinity of the grounding. The BA chart will have the notable light on Coco Island crossed out by hand in ink (Figure 3). All BA distributors are obligated to update the charts with pen and ink by hand, and this light was no longer functional after a BA notice to mariners in 2012. This light, nominally visible for 12 miles, is just a few miles from where Vestas Wind went aground.

Which brings us around to the echarts. Unless you are purchasing official BA ENC or RNC (called ARC), which are very expensive, then you are buying from companies that do not necessarily have the same BA standards for keeping their charts up to date—and I must add NOAA standards as well these days, as all NOAA charts are updated weekly now. You can’t buy U.S. litho charts anymore that may have been sitting in drawers for years. They are print on demand, and the masters, print and electronic, are updated weekly.

But we are considering foreign charts, or charts of foreign waters, made by commercial companies in the U.S. or elsewhere. In the case of these shoals, some of the electronic charts in use at the time of this grounding were not up to date in that they did indeed still show this navigation light, which could in fact, if there, have saved the day in this case. Hopefully it did not mislead any navigator.

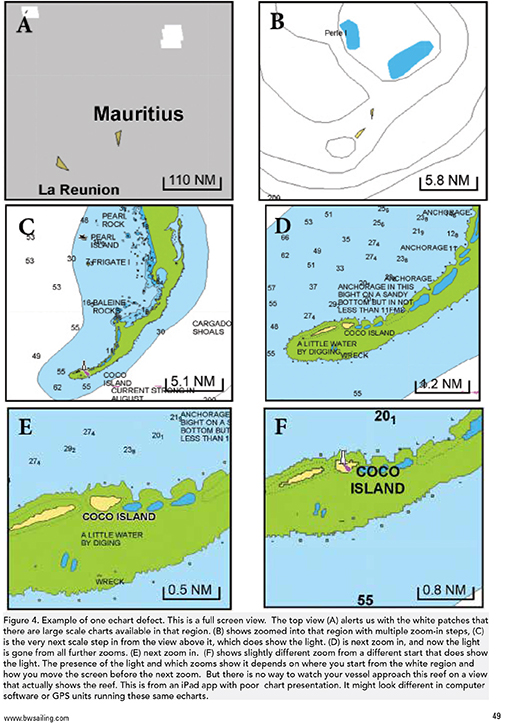

Even worse than that, some of the ECS chart packages did not layer the scales of this region very well, and in fact this point was brought up in the chatter about this region by several sailors competing in the race on other boats. Namely on one scale the Shoals did not appear at all and on the next scale up they filled the screen (see Figure 4). Thus if you did not zoom in at very near the right place, you would not see them at all—that is of course if you did not know ahead of time that they were there from your homework, and that this was indeed the primary issue of the navigation for at least a day or so, and as such have all sorts of backup contingency navigation in place, including radar and depth watch, besides GPS waypoints and tracks. In short, we are back to our rule.

No matter how bad the echarts and echart display might be, we cannot and should not blame them for anything. It is frankly our job as navigator to know such limits and work around them. When all is going well, echarts are an invaluable aid to navigation and racing tactics, but when the navigation is crucial, we need to back these up with other info. Figure 5, for example, shows a section of another commercial echart brand used on one of the race boats that also shows this light.

Another flaw of at least one echart program in use at this time was when right clicking and getting the data for this (non-existent) light it gave us all the information except how high it was. This height is crucial for predicting visible ranges of lights, so I would consider that a major charting error. Its official Light List number was also missing.

But suppose this is the situation: You have this echart on shore before the race as you plan your route, and you look at the light and find the height is missing. You know how important this light might be, so you must find this height somewhere. A first place to look is the NGA Pub 122, List of Lights. It covers all lights worldwide and it is free. In the latest 2014 edition of that book on page 566, sure enough you find that light. It is U.S. No. 32892, International No. D6681.6. It is listed as Fl(3) W, 30s, 27 feet above MHW, with a nominal range of 12 nautical miles. All this info is on the echart except the height of 27 feet. That would mean standing on deck at nine feet height of eye, you would see this light from about SQRT(9) + SQRT(27), or about eight or nine miles off. The 12-mile nominal range means it would show bright at that distance when it first comes over the horizon, and you might even “bob the light” by standing on the boom.

So you are better prepared—or so you would think. But not at all. This official reference book happens to be wrong. That light is not there; gone since 2012 as best I can tell. It is an error in the 2014 Pub 122. So we are back to our rule. This false confidence came from overlooking the main issue. The echart itself. When things are crucial, and you are using echarts from a commercial company that are not certified by the Hydrographic Office of that country, then the first step is to check the echart with a printed chart or an official echart.

At this stage, just a few days after the incident, we have no idea what led to the error. I have not heard of anyone directly involved with the boat blaming any echart, or in fact blaming anything. We are all human, and humans make mistakes. The extensive online chatter from distant observers, however, went straight to the charts.

The discussion here has been just one scenario. As it turns out some commercial echarts of this region are based on charts from the Indian Hydrographic Office, which happens to have an excellent chart of this area; No. 2503. Though basically the same as BA 1881, they do not have to scratch out the light by conscientious chart dealers, they have just removed it, so users of this brand of echart would not be confused by this issue—if they have been updated. I have not been able to test this, or how they zoom, and what meta data appear in these echarts. Also, we have to assume that whoever makes the echarts (regardless of source) do keep them up to date. Chart 2503 was new in March, 2014. Print on demand nautical charts from all nations are available online from EastView Geospatial (geospatial.com).

Remember too that of the half-dozen or so commercial companies that make worldwide echarts, some are known to be better for some regions than for others. We cannot learn which is best from advertising; we have to check with experienced users.

The Volvo boats had been in difficult conditions for a couple days negotiating a tropical disturbance with winds up to 30 knots. When approaching the Shoals, the wind direction was changing rapidly along the fringe of this Low (with clockwise winds in the Southern Hemisphere). The grounding took place about two hours after sunset, which at this low latitude was well past nautical twilight, meaning dark enough that the horizon was most likely not visible. Even in clear weather, you cannot see the reef downwind with waves breaking over it. There was a half moon about halfway up the sky to the east, which may have offered some light, but that near the Low this was likely hidden by clouds. I would have to guess that current was not a factor. Both the OSCAR five-day average and the latest RTOFS models gave current flowing to the west at about 0.5 knots at that time. They were off to the east so this current would have helped, if anything.

I want to stress that vector echarts certainly have much virtue and not just limits. Besides those mentioned, they offer custom displays and features that can indeed enhance safety not threaten it. Furthermore, all of the limits can and will eventually be removed.

For now we have the issues above in at least some systems, but these might not appear the same in all platforms—that is, in a computer versus in a tablet app, or integrated into the GPS display. On the other hand it could be that even the best echart navigation software has limits on this that are inherent to the specific echart package. There is also the question of how this might vary between ECDIS standard ENC and commercial vector echart products. Though in use now for quite a long time, there is still a lot to learn and a long way to go.

We will update this note online at bwsailing.com as related information becomes available.

David Burch is the director of Starpath School of Navigation, which offers online courses in marine navigation and weather at www.starpath.com. He has written eight books on navigation and received the Institute of Navigation’s Superior Achievement Award for outstanding performance as a practicing navigator.

In light of all the speculation about how Team Vestas Wind could go aground by error, I would like to offer one distantly related scenario that helps remind us of our fallibility and of the fate of circumstance. This was on a race boat having left Seattle on the way to Hawaii on a delivery to a race there. It was in fact a bigger boat than the VOR boats, and the skipper and several of the crew were as qualified as many VOR sailors. It had all the latest technology of the mid 90s.

In light of all the speculation about how Team Vestas Wind could go aground by error, I would like to offer one distantly related scenario that helps remind us of our fallibility and of the fate of circumstance. This was on a race boat having left Seattle on the way to Hawaii on a delivery to a race there. It was in fact a bigger boat than the VOR boats, and the skipper and several of the crew were as qualified as many VOR sailors. It had all the latest technology of the mid 90s.

We had rounded Point Wilson in Puget Sound after dark under power, and had about 70 miles to reach the ocean in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. I had set waypoints for the route out, which was very basic: travel along in the inshore zone, just out of the shipping lanes, facing inbound traffic on our right. Then I crawled into the bunk to get some rest so I would be fresh when we reached the ocean, which often has converging traffic and usually new current and wind to deal with. Unfortunately, as it turned out, it was a beautifully clear night in perfect conditions on an easy route with nothing to worry about.

Sometimes it is hard to go to sleep early, so there was tossing and turning, in and out of sleep. But from my bunk I could hear conversation in the cockpit very clearly. Somewhere in the half sleep I overheard someone say “I didn’t realize Smith Island Light would be so bright from here,” which bounced around in the mind for a few moments before I realized Smith Island Light is actually not bright from where we are at all!

I scurried on deck to learn that the crew was looking at Dungeness Light, essentially right next to us. We were inside of Dungeness Spit headed for the beach, with just minutes to spin around and head back out.

So now we get to say just what we read in the news today: How could this happen with such a trained crew on such a high tech boat? In this case, the base cause was the regular navigator had sat down at some point earlier with good intentions to review the waypoints, and to make a personal preference change to let the waypoints automatically advance to the next when within some set range. Although I strongly disagree with that approach (I think they should always be advanced manually) that was not the cause. Somehow in this process the crucial waypoint WP33 got deleted or skipped in the active route. We were essentially headed from WP32 to WP34 on a straight line.

But now we have to fold in all the special circumstances that let this type of error get by without being caught. Like many of the VOR boats we had an international crew, with some of the best sailors from around the world, and more to the point like many big boats with a crew of 9 to 11, most of the crew was not involved with the navigation at all. They assume this is a matter taken care of by two or three other members of the team, and they concentrate on their specialties. Of this crew we had several local folks who had sailed this route many times and would never have made this error, regardless of waypoints. But at times you can get combinations on watch or at the change of watch that might not include local knowledge. I do not recall these details; at least one person on deck knew the light, but they might have just come on watch. In any event, that is what happened.

Our target was a gently sloping sand beach, so chances are we would not have suffered serious damage, but a grounding there could have caused enough damage to cause us to miss the race, and cost all the investment of time and money that went into the preparation. The incident had been out of my mind for many years, but this recent grounding brought the memory back quickly.

So one answer to how such things happen is this: one fundamental error that would normally be caught, does not get caught, because of a series of peripheral factors that sadly come together at the same time. There is sometimes a fine line between bad judgment and bad luck.